Protein Overload: Are We Solving the Wrong Problem?

The surprising truth: most get plenty, benefits (if any) plateau, and the real risks might not be what you think.

It hits you the moment you walk into the supermarket. Rows upon rows of seemingly ordinary foods – energy bars, breakfast cereals, even yoghurts – now emblazoned with a single, powerful word: PROTEIN. Turn on your phone, and the message intensifies. Fitness influencers, wellness gurus, even figures with 'Dr.' preceding their names, are delivering urgent pronouncements. “Ladies, you’re NOT eating enough protein,” warns one Houston doctor to his tens of thousands of Instagram followers.

Another physician declares the official guidelines “totally wrong.” It’s a full-blown craze, a modern dietary gospel preached from podcasts and TikTok feeds. One prominent physician-author, who advises protein-related companies, dismisses the federal recommendations as "a joke," suggesting many of us need nearly triple the amount.

And we're listening. In just two years, the percentage of American adults actively trying to consume more protein leaped from 59 percent to a staggering 71 percent. We are, it seems, convinced we are deficient.

But here’s a curious thought, a little snag in this compelling narrative. What if, for most of us, this urgent problem we're rushing to solve… doesn't actually exist? What if the foundation of this protein obsession is built on something entirely different from our modern quest for bigger muscles and smaller waistlines? To unravel this paradox, we need to step away from the brightly lit aisles and glowing screens, and travel back to a world gripped by a different kind of crisis.

It’s 1940. The world is ablaze. Across the Atlantic, America holds its breath, knowing involvement is likely inevitable. Suddenly, questions usually confined to quiet university laboratories explode into matters of urgent national security. Forget tanks and planes for a moment; think about the people who build them, the soldiers who operate them. What does it really take to keep a person fuelled? Not just alive, but strong? How much Vitamin C? How much B1? How much protein? The scattered scientific knowledge of the time – insights gleaned from preventing horrific deficiency diseases like scurvy and pellagra – wasn't enough. The nation needed a standard, a yardstick.

Enter Lydia J. Roberts. A name perhaps lost to popular history, but pivotal. This University of Chicago nutritionist found herself at the heart of a committee convened by the National Research Council, handed an unprecedented task by the National Defense Advisory Commission itself. Forget academic curiosity; this was strategy. They needed numbers – hard targets for feeding soldiers, fuelling workers, guiding a nation's food supply through rationing and uncertainty.

Imagine the weight on their shoulders. The data was patchy – small studies here, animal experiments there, observations of what happened when people didn't get enough. From this mosaic, they had to forge something concrete. Their goal wasn't optimisation as we understand it today; it wasn't about sculpting the perfect physique or achieving peak athletic prowess. It was far more primal - preventing the widespread nutritional deficiencies that could cripple a nation at war. They were, quite literally, drawing a line in the sand against debilitating illness.

And they made a critical choice. Aiming for the absolute minimum needed to prevent disease felt too dangerous – people vary, metabolisms differ. So, they aimed higher. They estimated average needs and then, crucially, added a "margin of safety." They weren't just defining a requirement; they were recommending an allowance, a buffer designed to cover nearly everyone.

So, in 1941, the first Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) were born. Numbers on paper, forged in the heat of conflict, representing the best scientific guess for keeping a population resilient. Protein was there from the start.

Here's the fascinating turn. These wartime standards, designed for a specific, perilous moment, didn't vanish with the peace treaties. They lingered. They became the bedrock of nutritional policy for decades, the unquestioned foundation for dietary advice, food labels, government programs. The numbers evolved, certainly. For protein, the figure eventually settled around 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight for adults, largely based on meticulous, if somewhat criticised, nitrogen balance studies – measuring nitrogen in versus nitrogen out to find the point of equilibrium. It looked objective, scientific. But the core philosophy remained rooted in 1941 - setting a benchmark, with a safety buffer, focused primarily on preventing deficiency. It was about stopping the floor from collapsing beneath us, not necessarily about mapping the optimal height of the ceiling.

Now, fast forward to today, and confront the paradox. In developed nations, the vast majority of people aren't struggling to reach this 0.8 g/kg floor. We're comfortably above it. Take Australia, for example. The official RDI for adults under 70 sits at 0.84 g/kg for men (around 64g/day) and 0.75 g/kg for women (around 46g/day). Yet, national health surveys show the average Australian adult consumes around 95 grams of protein per day. To put that in perspective, a single, typical cooked chicken breast packs over 50 grams of protein. The average daily intake is nearly double that. That's significantly more than the baseline recommendation designed to prevent deficiency. Protein typically makes up around 18% of the average Australian's total energy intake, comfortably within the acceptable range. True protein deficiency? It's rare. The problem the RDAs were designed to solve has, for most, been solved.

So why the relentless push for more? Why are so many people trying to increase their intake? Because the conversation has shifted entirely. The modern proponents, the influencers and doctors calling the RDA a "joke," aren't talking about preventing deficiency diseases. They're talking about optimisation. They're leveraging research – often valid within specific contexts – showing that higher protein intakes can be beneficial... if.

If you're elderly, battling the natural decline in muscle mass (sarcopenia) and your body's waning ability to use protein effectively ("anabolic resistance"), then yes, consuming more (perhaps 1.0-1.6 g/kg) can make a real difference.

If you're an athlete, pushing your body to its limits, then yes, extra protein (1.2-2.2 g/kg) is crucial for repair and adaptation.

If you're actively trying to lose weight, whether through diet or medications like Ozempic, then yes, higher protein (at least 25% above the RDA, suggests one review) helps preserve that vital muscle mass as the pounds drop – though experts stress it needs to be paired with strength training.

These are the outliers, the specific cases where the wartime standard clearly isn't the whole story. But here's the danger: extrapolating these specific needs onto the general population. The average person isn't an elite athlete or necessarily battling sarcopenia. Yet, the message becomes universal: more is better.

And what about the limits? Is there a point where more isn't better? For building muscle, the evidence suggests yes. One study put middle-aged adults through rigorous strength training; one group ate 1.5 times the RDA, another twice the RDA. Both groups got stronger, but the extra protein offered no additional benefit. The gains seem to plateau around that 1.5-2 times RDA mark (1.2-1.6 g/kg) for most people. Pushing beyond that, chasing the extremely high numbers sometimes recommended, likely offers diminishing returns for muscle gain.

Then there are the safety concerns. The old bogeymen – wrecked kidneys, brittle bones – have largely been dismissed for people with healthy kidneys consuming up to around 2.0 g/kg/day. The kidneys adapt; it's not necessarily damaging in the short term. But that "healthy kidneys" assumption is where things get murky.

High fructose intake via sugar and HFCS, in particular, is strongly linked to kidney strain via pathways involving uric acid. The result is that more than one in seven US adults is estimated to have chronic kidney disease, and a shocking nine out of ten don't know it. So, we aren’t really starting with a baseline of perfectly healthy kidneys across the population. Which means the safety assurance for high protein sis on shaky ground. Piling a heavy protein load onto kidneys already stressed by sugar is likely to be a risk we're seriously underestimating.

Even if your kidneys are pristine, remember: protein has calories. Excess protein your body doesn't need for immediate building or repair gets converted and stored, likely as fat. And relying heavily on processed protein sources – those ubiquitous bars, shakes, and enhanced yoghurts – often means consuming significant amounts of sugar negating the benefits and adding to the metabolic burden.

The source matters profoundly, and not just because of processing. Think about where much of our protein actually comes from. In Australia, the biggest chunk (around a third) comes from meat, poultry, and fish. But the next largest contributor, at about a quarter, is cereals and cereal-based foods. Dairy chips in around 16%, and vegetables about 8%.

Is protein from your breakfast cereal or bread the same as protein from an egg or a steak in terms of its usefulness to your body? Not really. Meat and dairy provide 'complete' protein, offering the full deck of essential amino acid building blocks your body needs, in a highly digestible form. But cereals typically offer 'incomplete' protein, often lacking sufficient amounts of certain essential amino acids (like lysine). Their protein will also be less digestible due to fibre content. This doesn't make cereal protein bad, but it means relying heavily on it requires more thought – ideally by ensuring some complete protein sources are also in the mix. It's not just about the grams; it's about the quality and the company the protein keeps.

So, we circle back to the paradox. We live in an era of protein abundance, yet we're caught in a frenzy of perceived deficiency, urged on by voices focused on optimisation, often overlooking the nuances of plateaus, protein quality (is it complete? easily digestible? where is it coming from?), and underlying health risks like undiagnosed kidney issues exacerbated by our sugar-laden diets. The wartime yardstick, designed to prevent the floor from collapsing, is being wielded in pursuit of ever-higher ceilings, sometimes without checking if the building's foundations are sound or if we're using the best quality materials.

What, then, is the real takeaway? Do you, the average person reading this, need more protein? Probably not. You're likely already exceeding, by a significant margin, the level set to prevent deficiency (Australians average ~95g/day vs RDIs of ~46-64g). But if you're in one of those specific groups – building muscle (aiming for that 1.2-1.6 g/kg sweet spot where benefits peak), preserving muscle during weight loss (hitting at least 25% above RDA, with strength training), or fighting age-related decline – then yes, a strategic increase makes sense.

So, let's be brutally honest. Do you need more protein? For the vast majority of people, the answer is a resounding NO. Stop kidding yourself. You're almost certainly getting more than enough already, blowing past the levels needed to simply avoid deficiency. Unless you're a professional athlete dedicating your life to performance, deep in a medically supervised weight-loss program specifically targeting muscle preservation, or facing diagnosed age-related muscle wasting, chasing ever-higher protein numbers is likely a complete waste of time, money, and metabolic effort. Remember the plateau? Shovelling in more protein doesn't magically equate to better results.

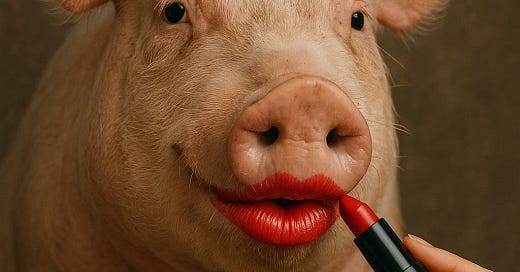

Forget the obsessive gram-counting and confront the real issues: protein quality and your overall diet. Stop being suckered by cynical marketing that slaps a 'high protein' label on what is essentially sugary junk food. That protein-enhanced chocolate bar? That dessert-flavoured yoghurt? They're often loaded with sugar and seed oils that actively harm your health. The protein claim is frequently just lipstick on a pig.

Demand better. Real protein, the kind your body actually thrives on, comes from whole foods: lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs, and unflavoured dairy. Understand where your food comes from. Get real about your actual needs versus the fantasy fitness goals sold online. And take a hard look at your entire diet – especially the sugar – and the potential damage it's doing to your body, including your kidneys, which might already be struggling silently. It's time to ditch the hype, reject the processed crap, and start eating real food like intelligent adults.

Well said, and it needed saying.

Appetite and instinct can guide us once we are re-committed to actual meals with actual food. With that, I use the wholeness measure, which, put simply, means don't drink orange juice if you can eat an orange.

This mattered less in my youth. In my seventies, it's critical. I don't know what colds, flu or indigestion feel like, but I can find out in a hurry just by spending more time in those middle aisles, if you know what I mean.

It's almost like we just need to eat less processed crap, and not worry too much about much else.